Reminiscences of Ware’s Past Part 8 - 1997

My sister Eileen put me in touch with David Perman and he sent me copies of Henry Page's excellent booklets published by the Ware Society (Reminiscences of Ware's Past Nos. 6 & 7). Scores of memories were triggered off for me while I was reading these booklets - mind pictures of characters most of whom, alas, have left us for good and of scenes many of which have similarly vanished.

I was also struck by the similarities between Henry Page's career and my own. We both started work about the same time - he for the erstwhile Ware Urban District Council and I for the old Rural Council and both (apart from the War years) spent the remainder of our working lives in local government finance, qualifying with the Institute of Municipal Treasurers & Accountants (now the Chartered Institute of Public Finance & Accountancy). And yet we never knew each other. One reason for this was that he was a "St. Mary's boy" whilst I was "Christ Church" and that, in a quite definite way, identified us with distinct areas of the town but with the old town centre, of course, in common.

In course of time, I became the "poor filing clerk" referred to on page 5 of his Reminiscences No. 7- but more of that anon.

The Poor Filing Clerk Chapter 1

Early Days In Musley

I was born (there is no other way to begin, is there!) in Tottenham in January 1918. My father had by then served about 20 years in the Royal Navy. From leaving school in Edmonton until a young man he had worked at Enfield Lock in the old armaments factory so on joining the Navy it was natural for him to become an armourer. He served all over the world, latterly on HMS Cyclops, a repair ship which was part of the Royal Navy presence in Archangel at the time of the Russian Revolution. He married my mother, Florence Dye, who was then living at Tottenham. Whilst my father was seeing out his 22 years with the Navy my mother brought me at the age of six months down to Ware, where we lodged for a time in Trinity Road with a very nice family called Doxey who were keen Chapel people. Joan Doxey and I were of an age and later attended Musley Central School together.

My mother's father, Arthur Dye, was born in a house near the Tumbling Bay. His father was a lock-keeper there and there were so many children (8 or 9) that my grandfather said that, holding hands, they could stretch across the Tumbling Bay! Arthur became a lock-keeper himself at Ware Lock, where my mother was born. Her parents decided to name her after the next barge to come through which they knew to be either the "Florence" or the "Frances Pelham". In the event the "Florence" arrived first and my mother was so christened! Arthur Dye nearly didn't become my grandfather when, as a young man and doing a postman's job, he jumped into the river for a swim on a hot day only to find himself sucked under by a passing barge. He was lucky to escape alive.

My mother's maternal grandmother lived to be 84 and died when I was about 5 years old. Her married name was Booth and the Booths came from the Rye Park area. As a result we used to visit the Old Rye House fairly often, where the dungeons and instruments of torture always fascinated me. A plot (unsuccessful) was hatched there in 1683 to murder King Charles Il and his brother (later James Il). On my father's side, little is known except that they emigrated in mid-Victorian times from Ireland and settled in London.

Referring back to Rye Park, other memories include the extensive watercress beds and, a little later, the Frogley brothers, who helped to put dirt-track racing in this country on the map. About 1924 there was a wonderful pageant in the grounds of the Old Rye House at which the life and times of the Plot were re-enacted, with the "county" families and other notables appearing (mostly mounted) in the splendid clothes of the period. It rained most of the time, but it was a marvellous spectacle.

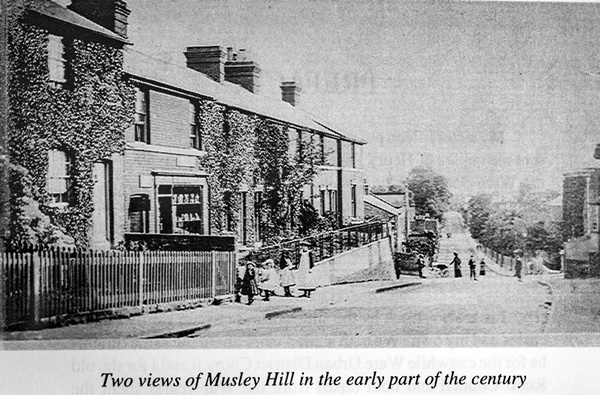

After a year or so (by which time my father had come out of the Navy) we moved round to No. 46 Musley Hill, where my sister was born. Between us and next door was a passage with a dust floor which was most unpleasant. Our rear garden backed on to a disused gravel pit the depth of which to a small child seemed immense. A short walk from the back gate brought us to my father's allotment garden, between the backs of Musley Hill and Trinity Road houses. The "local" was the Jolly Gardener, a little further down Musley Hill, and this was used by my father for many years. It had a back entrance to accommodate the thirsty allotment holders.

My father's best friend was one Charlie Crew, a Canadian who had stayed on after the Great War and married Jessie, a very jolly Cockney. They kept a sweetshop between the Jolly Gardener and the Musley crossroads. Charlie was a great character who, unfortunately, suffered severely from a heart problem. He also spent quite a bit of time in the Jolly Gardener. Charlie made wonderful ice-cream of the custardy variety for the freezing of which ice-blocks were delivered which were stored in an earth cellar dug into the back garden and covered by a massive wooden lid. In winter he sold pease pudding which Jessie made. They had splendid family parties at Christmas at which Charlie always recited the whole of the "Shooting of Dan Magrew"!

The general shop on the Musley crossroads also served as a sub-Post Office and was kept in the early 1920's by people called Scott. I associate this with my first conscious embarrassment - at the age of 4 years. I was sent down to Scott's with requirements written on the back of an Admiralty envelope with money inside. When I returned home empty-handed I confessed to posting the envelope in the letter box there was a quick trip down to Scott's to get the post box opened!

Next to No. 46 (downhill) lived the Storey family. The old man, like many Ware people in those days, had to have periodical stays "up the San." with tuberculosis, or "consumption" as it was commonly known. "The San" was, of course, the Ware Park Sanatorium. A son of the family (known universally as Sonny) was a very good distance runner and usually won at local athletics meetings, one of which was held annually on Whit Monday at Rye Park. On another tack, I used to wonder why, if there were strangers around, the old man always kicked the dog into a sort of locker in the back garden constructed mainly from the metal enamelled advertisements such as "Stephen's Ink", which one used to see fixed to shop walls. Later I learned that either he feared a visit from an RSPCA Inspector, or from a policeman to ask why he hadn't a dog licence.

Five or six houses up from us was Fred Pavey's bakery and shop. I believe Fred had previously farmed out towards Wareside. He also was a customer of the Jolly Gardener and therefore a good friend of my father. His bakehouse extended backwards down his garden and if he had any dough left over he would make it into a small cottage loaf and put it into his side-window which I could see from our back, whereupon I would trot round to Fred to collect it. Fred's and all other houses in that row were served by privies at the end of the gardens - uninviting at any time but particularly so in bad weather.

Nearer the top of Musley Hill and in a better class detached house lived Mr Govier, teacher of the piano and splendid organist at St. Mary's Parish Church. Always well-dressed as befitted his station, he too was well acquainted with the Jolly Gardener and various other similar establishments. I am sure it was more than a fable that during the sermons at the services at St. Mary's he quietly swung round off his organ seat and went through the vestry and across the road to The Cabin public house in Church Street for a quick tot. At my father's invitation he once came round to our house (after we had moved to Bowling Road) to hear my sister play the piano. Swaying slightly and with more than a whiff of whisky in the air he solemnly announced that she was a "Mozart in petticoats!" Good though she was, she didn't quite merit that description! But Mr Govier was an exceptionally fine organist and when he was really in the mood the old Church fairly reverberated with sound. He also ran a very good choir at the Church. Two of the leading choristers were Bert Wright (baritone) and Cliff Parker (tenor). Henry Page refers fully to Bert in Reminiscences No. 7. Cliff Parker was the Ware Relieving Officer.

Right at the top of Musley Hill, opposite to the old Central School, was a walled meadow, one side of which ran down Musley Villas towards High Oak Road. When I was lifted up I could see from over the wall that the grass was lush and green with lots of buttercups and was grazed by a small number of beautiful Jersey cows, owned, I think by one of the ladies living in the Villas. The cows had a thatched cowshed to shelter in. Musley Villas were definitely above our class. To an under eight-year-old the inhabitants - on the rare occasions when any were seen - all seemed to be elderly ladies of some elegance. One Villa had a mulberry tree in the front garden, and it was altogether an agreeable area. The cows were regularly seen to by an elderly man who rode an equally elderly bicycle with great concentration in a slow, dead straight line. On one occasion I watched fascinated from the opposite side of the road as, without turning his head or even a hair of it, the old man rode straight over a leg which a boy sitting on the pavement had thrust out in front of the front wheel.

One other memory of living on Musley Hill was of the Ware Procession, which made its way round the town on, I think, August Bank Holiday. I can vividly remember "Greasy" Talbot, who owned a motor repair business in the High Street, sweltering on the open top of a double-decker bus dressed in a Michelin Man outfit and being driven slowly down the hill. That must have been about 1922.

A lot of the transport was, in the early 1920's, still horse drawn. The beer was generally delivered by horse and dray although one of the brewers also had a beautiful Foden steam engine in use. Carter Paterson was the nation's main carrier, it was they who delivered my father's sea chest but because of the steepness of Musley Hill the driver wouldn't come higher than Scott's on the corner. When going down steep hills frequent use was made of skidpans which were steel shoes placed under wheels to add friction to slow the progress. At such places it was common to see roadside notices threatening penalties for allowing the skidpans to damage the road surface. Most wagons also had brakes which were applied by handwheel. On one occasion when coming up New Road with my mother we were near to Mrs Woodward's shop when I saw the frightening sight of a runaway horse galloping down the hill with just the shafts and two front wheels of a wagon behind it. Providence kept it to the road otherwise there would have been a number of casualties.

Mrs Woodward was a short, quiet lady with very thick lenses to her spectacles and she sold a whole jumble of goods. In the smaller of her two windows confectionery of various kinds was displayed including small, dry, tiger nuts, dry, black locust beans and small strips of Spanish wood all of which seemed in a strange sort of way to reflect the personality of the good lady herself.

I really don't know why I, or anyone else, bought them. They had some sort of taste but the process of chewing them was most unrewarding! I suppose we were always interested in anything that was even halfway edible and could be bought for a ha'penny. But gobstoppers, sherbert dabs and liquorice laces were a much better buy.

Reverting to the then transport, on one or two morbid occasions I saw the "dead horse cart" carrying a sad carcass. The RSPCA were active and on one occasion a horse which they found unfit for work was put down by humane killer close to Fred Pavey's bakehouse. Boys used to hitch rides on the tailboards of coal and other wagons. Passers-by would shout "Whip behind, mister!" to draw the driver' s attention to them and the drivers would playfully flick their whips to get rid of their unwanted passengers. In the early 1920's there were still one or two horse-drawn carriages plying for hire from the rear of Ware Railway Station. One of them was an all-wicker affair. My great-aunt, Alice Dewbury, once took me for a ride in one of them. I am reminded that we dubbed the Stationmaster of those days "Mr Kruschen" because of his resemblance to the little man who appeared on the advertisements for Kruschen's Salts, a fizzy concoction which "did you good!".

The carriages were soon to be replaced by motor taxis. Another ride which I much enjoyed was in a donkey and cart driven by Charlie Crew but loaned from Tommy Powell who had an undertaker's business in Baldock Street (now in Watton Road). We drove round the country lanes to Wareside. A character known as "Pincher" used to lurk round the many bends on these roads to wave the few motorists safely round them in the hope of earning the odd copper.

Chapter 2 Growing Up In Bowling Road

In 1923, when I was 5 years old and my sister 3, we moved down to No. 27 Bowling Road let to us at a rent of 12/6d per week including rates. This house was a slight upgrading from No. 46 Musley Hill. More to the point, it was nearer to my father' s work, Christ Church infants school, and the town.

When my father first came out of the Royal Navy he got a job with Pemberton-Billing, in what later became the Swain Envelopes factory in Crane Mead, making some sort of patent kitchen stove. Pemberton-Billing was very good to his employees - too good, as my father said later. The result was bankruptcy. Round about that time there was a General Election in which Pemberton-Billing put up as an Independent against Admiral Seuter (Conservative). No punches were pulled and Pemberton-Billing had an Election "Anthem" which has stuck with me ever since:

"Vote, vote, vote for Pemberton-Billing.

Who's that knocking at the door?

If it's Seuter and his wife

We'll stick them with a knife,

And we won 't vote for Seuter any more!

Hardly tasteful - and singularly unsuccessful - Seuter got in easily.

My father then went to work for Bob Dewbury, Builder & Undertaker and my mother's cousin. The workshops were in Bowling Road (Kibes Lane end). On the ground floor was situated the woodworking machinery. First run by a gas engine with a huge flywheel, there were circular saws, a band saw and a planing and moulding machine. Nowadays mouldings are, of course, bought in but Bob Dewbury made his own. They could be varied by changing the profile of the cutting blades. My father worked the machine-shop - but not without incidents.

On one occasion a cow, being driven along Bowling Road, turned into the workshop entrance and, before anyone could do anything, made its way into the gas engine area and everyone waited for it to put its head through the spokes of the flywheel. Fortunately, it made its way out in its own time and a horrible mess was averted. On a less fortunate occasion my father evidently failed to fasten the revolving moulding blades properly and they flew off the spindle and removed the tops of the fingers of his left hand. He could easily have been killed. He had to walk the half-mile or so round to Dr May's surgery in New Road to get the necessary emergency attention prior to being taken into Hertford County Hospital. Bob Dewbury's brother, Ned, also worked at the Bowling Road workshop. He was a very good carpenter although much of his time was taken up with the rather morbid job of making coffins. Ned lived with his wife Florrie in the sexton's cottage near to Great Amwell Church, where he served under Rev Harvey, of whom more later.

Times became difficult for the Building trade and unfortunately Bob Dewbury got too far behind with stamping his employees' unemployment, health and pensions cards and became bankrupt. All the employees lost their jobs and it was a difficult time in which to find work. By now in his mid-50's my father bought a motorcycle and rode daily to and from St. Albans where he had found work at Dumpletons.

In due course that finished and he got a job at Vauxhalls at Luton, only coming home at weekends. The period 1929-34 was indeed a bad period economically and socially, with much unemployment.

Children's Games

Apart from the economic problems which resulted in my mother having to manage on a low income, life for me at Bowling Road was pleasant enough. We children followed the seasons in our games. In the Autumn spinning tops were very popular. They were started by a sudden pull on the string which had been wound round the top. They were then kept spinning by whipping them with the string which was fastened to a wooden handle. There were various shapes of tops. Most of them were made of wood but there were some of tin which whistled when they spun.

Hoops (of wood or metal) were run up and down the roads, where there was, of course, far less traffic than today. The hoops were propelled either by being struck with a wooden stick or by pushing with an iron "schemer" which was a metal hook inserted into a wooden handle. Generally speaking, the girls used wooden hoops and the boys metal ones. "Pop-guns" also had their place in the calendar. Plenty of elder bushes grew in the hedgerows and to make a pop-gun a piece of stem about 9" long was cut out with a diameter of about an inch and a half. This would form the barrel. In the centre was about a quarter of an inch of soft pith which was removed by burning out with a hot poker or wire leaving the bore quite smooth. Next came the rammer, usually a length of dowel rod pushed into a large cotton reel. The rod was cut off about I " short of the length of the barrel and the end was burred over by being moistened and hammered against brickwork. The resulting rammer moved smoothly up and down the barrel, the end being kept moist and splayed to make it fairly airtight like the plunger of a bicycle pump. The choice of ammunition was usually between a plug of wet paper or an acorn rammed hard into the end of the barrel. When the rammer was smartly pushed home the missile came out with a loud "pop" and with considerable force. These pop-guns were quite easy to make and were favourite play-things for boys.

When the fruits of the horse chestnut trees were available in the Autumn the game of "conkers" came into its own. A hole was skewered through the "conker" which was threaded with either a piece of string or a bootlace in which a knot was tied below the conker. Each player took turns to hold his conker steady at the end of the string. Whoever's conker remained eventually intact was the winner. There were, of course, various complications such as shouts of "stringers" when the strings tangled (the first to shout was entitled to the next hit) and scores could be cumulative - at the outset the players declared how many victories (if any) their conker had had and the winner was able to add his opponent's number to his own. Frequently the contestants suffered nasty cracks on the knuckles from errant swipes!

Cricket and football were played in the street. For us, the favourite area was in Bowling Road just before its junction with Vicarage Road. As many as twenty or so children milled around most evenings kicking whatever ball they could get - usually an old tennis ball. Cricket often took the form of "hot rice" where one person defended himself with a cricket bat against a ball being thrown at his body. When he was hit the bat passed to the thrower.

Play was suspended when the local bobby, P.C. Briden, hove into view or when a householder stopped the game following one of their windows being hit with the ball. Very seldom was one broken. The girls usually played hopscotch, skipping or five-stones, according to the seasons. The hopscotch frames were chalked on the pavements - not a very tidy sight I am afraid. Sometimes we played in the school field between Bowling Road and what was then Christ Church School. To do this we had to climb over the spiked railings which was quite a hazardous business. The street was much less trouble.

Much fun was had with cigarette ("fag") cards. Apart from the collection of whole sets, spare cards (unless used as swaps) were used for various games, mostly entailing flicking the cards either to knock down a card leaning against a wall, or landing on a card or cards. Success resulted in a number of cards changing hands in favour of the winner.

At a fairly early age I found my way into the pleasure of reading. The Public Library facilities were provided in an upstairs room at the Priory and the dimly-lit array of shelves with the rather musty smell of elderly books was a treasure-house to me. From the age of nine years or so G.A. Henty was easily my favourite author. Through his writings I travelled the world and, in my mind, stood beside his characters in heroic undertakings, from the Siege of Rhodes by the Knights of St. John to the Dash for Khartoum and from the Russian Snows (Napoleon's retreat) to be with Buller in Natal! 'Full of sieges, of the smoke, the din and dust of battle' commented the "Standard" at the turn of the century. The Librarian in the late '20's was Mr Charles Dewbury (no relation of ours), a kindly man with a beard, given to good works and Superintendent of the Ware contingent of the St. John's Ambulance Brigade.

Guy Fawkes Day And Christmas

Guy Fawkes Day and, of course, Christmas were highlights of the Winter. We all bought fireworks (according to our means) and they and bonfires flourished on the night of 5th. November. Children chanted seasonal jingles such as:

"Please to remember the 5th. of November,

The Gunpowder Treason and Plot."

and

"Guy, Guy, Guy, never come anigh

Stick him on a lamp post and there let him die!"

Grown-ups were accosted by the poorer children equipped with monstrous effigies of Guy Fawkes with the plea "Penny for the Guy, Mister!" For several years I took my fireworks round to Bluecoat Yard where a friend of mine, Bob Evenden, lived in one of the row of cottages on the left-hand side which, years before, had housed pupils of the branch of Christ's Hospital School, now known as Place House. In those days we had no idea of the age and history of this building. As we have since learned, it was built in the 14th. century and was at one time the Manor House of Ware belonging to the Crown and had distinguished occupiers over the years before being acquired by Christ's Hospital towards the end of the 17th. century. They moved out a century later and eventually sold the estate. Full details are given in a very commendable booklet prepared by the Bluecoat Yard Residents Association. I was also friendly with Philip Chapman whose father had a Nursery Garden at the end of Bluecoat Yard and a greengrocery shop in the High Street.

Christmas was a great time for most children although its degree of sophistication varied, of course, according to the family's affluence, or lack of it. It began with each of us getting an orange to take home from school. One year (it may have been more) the Ware Chamber of Trade ran a competition in which one had to spot one item in a shop window which was "foreign" to that particular shop. I pressed my nose against numerous shop windows and won a voucher as a result. This I had no hesitation in presenting at Wells the Ironmongers in the High Street. I was well into Meccano and Hornby trains at the time and the voucher bought me another railway truck. I loved going into Wells when I had any money to spare - their display of Meccano parts, especially gearwheels, always fascinated me. It was always my job to get the holly and a small group of us used to cycle up to Walnut Tree Walk, near Great Amwell, where the best holly bushes were. On Christmas Eve the "Waits" in the form of either the Ware Town Band under their conductor Mr Edwards or the Salvation Army Band, went round parts of the Town playing carols. In those days Christmas started on the evening of Christmas Eve and finished on Boxing Day - quite unlike the extended period of today and in some ways more sharply meaningful.

Ware Cinema

A great favourite for all of us children was the Ware Cinema in Amwell End - unique, in my experience, with its flat floor. Outside were half a dozen stone steps topped by a pair of metal latticed sliding gates. From 1.30 pm. onwards we gathered on Saturday afternoons like a flock of roosting starlings, waiting for the gates to open at 2.00 pm. We knew that there would be plenty of room for us all but that did not prevent us from pressing upwards on the steps for all we were worth. Those at the very top held tightly to the gates, the rest held on tightly to each other. Perhaps a swarm of bees would be a more apt description.

At 2.00 pm. Mr Snow, the attendant, unlocked and forced the gates back. How fingers were not broken in the process I do not know. With a great shout we surged forward, paid our 2d. entrance and rushed through the doors and down to the front seats. Then the real noise started - everyone shouting in excited anticipation. Most chewed "suckers", paper bags and other missiles were thrown about and some ate pomegranates and spat the pips at the necks of those in front of them. It was chaos.

Occasionally someone would explode one of the small bullet-like "bombs" in which caps were fired. This would almost certainly cause the lights to be switched on and Mr Snow, complete with a Kitchener moustache and commissionaire's uniform, would march in and threaten to stop the show and send everyone home. This reduced the noise for a time - but not for long.

We saw lots of wonderful black and white films - with cowboy Tom Mix, Charlie Chaplin and Jackie Coogan, Buster Keaton and other famous figures. For the evening performances the Ware Cinema boasted a pianist who played away with music to suit what was happening on the screen. I do not think that happened at the Saturday matinees - there would have been little point, the noise level being what it was, cheering the hero and warning him to "Look behind yer!" and booing the villain. Later, of course, came the talkies which didn't allow the same degree of audience participation and much fun went out of those riotous Saturday afternoons!

Picnics

Picnics were very much in vogue. When the hay had been cut in May or June families used to picnic in the hayfields, making "houses" (circles) out of the loose hay and eating their picnic teas inside them. This was useful for the farmers in that their hay was turned, which helped dry it out prior to its being carted away for stacking. For us, the nearest hayfields were between High Oak Road and the Round House. On one disastrous occasion I had made one such grass house in the garden of an elderly aunt at Little Amwell and jumped in without realising that my aunt was already sitting inside with teacups, plates and the rest. I was in mid-air when I saw with horror what was going to happen - which it did! Our other relations, the Dewburys, had an early descendant of the T-type Ford and occasionally took my sister and me on picnics towards Waters Place. The novelty of the car ride plus the picnic made for very enjoyable occasions.

A Local Hero

Near to the Round House was Great Cozens, occupied by Sir Thomas Devitt and his widowed mother. He was famous as a Rugby player and was, I think, capped for England. He was then a dashing young man and drove a Sunbeam motor car - then the top of the sports cars. A few years later Major Seagrave was to use his Sunbeam "Golden Arrow" for his successful bids for the world speed records. It was no coincidence, I feel, that a year or two later, I was to see Jack Hobbs, the famous cricketer, sitting in a Sunbeam car eating a sandwich along the Wadesmill Road on his way no doubt to his original home in Cambridgeshire. Obviously if you were a top sportsman the Sunbeam was the car to have! Just prior to my writing this a notice appeared in the Daily Telegraph announcing a memorial service for "Lt. Col. Sir Thomas Devitt (Bart.)" Looking in Who 's Who I saw that it was the Sir Thomas we knew, having been born in 1901, which meant that he would have been in his mid-20's in the times of which I am writing. The family was in shipping and the notice showed that Sir Thomas had in more recent times lived near Colchester. His mother married Rev. Lloyd Phillips, Vicar of Ware St. Mary's, a rather flamboyant but attractive man, whose light grey suits contrasted with the dark cloth of the more traditional Rev. Frank Hobson of Christ Church.

Supporting Ware Football Club

When I was quite small - probably about 5 years old - I have a rather dim memory of my first acquaintance with Ware Town Football Club when my father took me to see them play on a ground which I think was well up Watton Road. Soon after this the Club moved down to the Bury Field. Here, after a couple of years, I became a regular supporter. A friend of ours had the job of housekeeper/cook to Mrs Hitch who lived in Baldock Street. The grounds of this pleasant house stretched right back to the football ground. The boundary was a wall topped with railings and I stood on a box and had a marvellous view of the pitch from behind one of the goals. In those days Ware had a very strong team playing in the second division of the old Spartan League. In one of their most successful seasons - possibly 1925 or 1926 - they ran up very high scores in most matches reaching double figures on several occasions.

Their centre-forward (oh, for a return to those well-established and straightforward positions!) was named Dearman and I think he worked for the old Northmet Electricity Company. In this particular season he brought his tally of goals scored for the Club to something in the region of 100. The team qualified for promotion but Dearman was leaving the Club at the end of the season to live at St. Neots. The Secretary of the Club was Ernie Whybrew, who lived two doors away from us in Bowling Road. Ernie had a club foot but somehow managed to ride a bicycle. He worked in the office of Hitch's the builders who were very good supporters of Ware Football Club, several of the players finding employment there. I well remember Ernie talking to my father over the garden fence one Sunday morning about the question of whether or not to take promotion to the higher division. In the event the Club decided that with the likelihood of reduced playing strength the next season they would stay in the same division - "better a big fish in a small pool”. I also remember that on that occasion he mentioned the name of Charlie Martin, a new signing from, I think, Rye Park, of whom they had great hopes. Though not in the Dearman goalscoring mould Martin was a gifted footballer and played for Ware for a number of years.

Other names of earlier players which come to mind are, firstly three goalkeepers - Saxon, Gordon Bottoms and Ted Dennis who played for the Club in that order. They were to be followed later by Ches. Powell, son of Tommy Powell, undertaker, who went on to play for Barnet in their great amateur days and to win an Amateur Cup Winners medal. Other early names were "Puller" Devonshire, Rolfe (a Thundridge schoolteacher), little Sammy Goodey and "Tudge" Barker, a fine athlete and a dashing right back. "Puller" Devonshire was a considerable character and a great Club man. After his playing days he appeared as linesman and, one is bound to say, did his best for the Club in that role! Woe betide anyone on the opposing side who Puller thought was playing "dirty". Egged on by the home supporters he would contrive to "flag" the player concerned on some pretext or other and the temperature of the game would rise accordingly. During the week Puller Devonshire delivered coal for Warrens.

Apart from these episodes the atmosphere was by no means always sweetness and light. The Lea Bridge Gas team were, deservedly or not, always regarded as a rough team and on one occasion the wife of one of the Ware officials became so incensed that she ran onto the pitch and struck their goalkeeper over the head with her umbrella!

Cricket

Cricket never really took off in Ware itself, although it was much played in the surrounding villages. However, Allen & Hanbury's ground was excellent and they fielded two teams. One of their foremost players was Harold Gillett, their groundsman. There was a team of sorts identified with The Town Football ground on the Buryfield but the wicket was poor. The only distinguished thing about the Ware team in those days was the presence in it of one "Diddy" Beecham who lived at Hertford and played football as goalkeeper for Fulham FC. Cricket was also played to a good standard at Presdales.

Sundays

The disruption caused by World War I and the frivolities of the 1920's resulted in a decline in Church attendance generally, but many families continued to attend at least one Service on a Sunday. Best suits and dresses were de rigueur. In Ware, Chapels and the Catholic Church seemed better able to retain their congregations than the Church of England and the "working classes" were less well represented than others. Father Macerone (inevitably "Macaroni") was much loved but his dream of a Roman Catholic Church in King Edward's Road rather than the then hut only materialised some years later.

A significant proportion of children attended Sunday School. I am afraid to say that the denomination one chose owed much to its recent reputation for Sunday School "Treats"! In my case the Wesleyan in New Road held the most attraction. Sometimes the denominations joined together for the Summer Treat. Presdales, then home of the McMullens, was often used for this and there were races and other sports and, of course, teas. On one occasion buses (double-deckers with open tops) took us to the grounds of Brocket Hall for a really big jamboree. Driving up Chadwell Hill with a full load of shouting kids was too much for our particular bus and we had to get off to lighten the load whilst it grunted and jerked its way up the hill. At Sunday School we had booklets into which we stuck religious stamps - one for each attendance. Our entitlement to attend "Treats" depended upon having sufficient stamps on the card.

One of the agreeable characteristics of life in those (almost) pre-car and pre-television days was the family Sunday evening stroll, sometimes in the company of friends. There were two main focal points in Ware for this - one was the Priory grounds and the other was Fanhams Hall. The Priory was always open and Fanhams Hall gardens were open on a number of occasions in the Summer months for the benefit of the Nursing Association. At Fanhams Hall a particular point of interest was the Japanese Garden. Both at the Priory and at Fanhams Hall the Ware Town Band, under its conductor Mr Edwards, played throughout the evening and people in their scores strolled and met friends and acquaintances. Head Gardener and general factotum at the Priory was Bob Jackson who came originally from Suffolk and was known there by my father from his Navy days at Shotley. Under Bob the gardens were immaculately kept, the lawns were particularly fine. On Sunday evenings he was in attendance with a walking stick with which he preserved commendable discipline among the more boisterous children. They were not allowed to spoil either the adults' enjoyment of a very pleasant scene or his lawns and flowerbeds. There was an adjacent small recreation ground equipped with swings and roundabouts as well as see-saws on which those children who wished could work off their surplus energy. Apart from the Priory or Fanhams, lots of families just walked about the town to see new developments etc. One favourite walk was along Priory Street past the "Mill" (Allen & Hanbury's) across the bridge over the Lea and along the opposite towpath as far as the Toll Bridge — from whence it was but a short step to the Saracen' s Head for refreshments before returning home. Sometimes we walked across the fields to The Fox public house at Babbs Green towards Wareside or across the Golf Links to the Halfway House.

Scouting

Scouts and Cubs, Guides and Brownies were popular. I joined the 3rd Ware Group as a Wolf Cub and eventually became Pack Leader of which I was naturally quite proud. We met every week on an evening at the Mission Hall, Amwell End. We paid a "sub" of a ha'penny per week and the evening was split between drills and instruction (semaphore, and morse signalling, knots and so on) and games. We all strove for proficiency badges in a whole range of activities. The Scoutmaster for the 3rd Ware was Jack McNaughton whose father had a small Barber's shop on the corner between the Saracen's Head and the Toll Bridge. At 4d. a haircut for adults it was the cheapest in town. For boys it was 2d. and they all emerged as look-alikes, close-cropped with a fringe in front! The Cub-master was Jack (Doughy) Taylor who lived in London Road and the Assistant Cub mistress was a Miss Hatherill. "Chalk" and "Paper" chases out into the surrounding country were popular in the better weather and for the older ones (and those whose parents could afford it) there were Summer Camps (Broadstairs and Clacton were favourites) and sometimes a weekend camp. One of these took place in Major Shepherd-Cross's grounds, attached to Sprangewell at Thundridge. We were warned not to disturb the Major's pet Dabchick (a Little Grebe) on its small pond. Fortunately, no-one did. Somebody made a huge jelly in a washing bowl which turned out to be incredibly runny and attracted a mass of wasps. Not surprisingly, one of the Cubs - Dave Climo - was stung in the mouth which could, of course, have been dangerous but he came to no lasting harm. We frequently joined with other organisations on civic occasions and in particular, at the annual Armistice Day Service at the Ware War Memorial.

Kibes Lane

Kibes Lane was part of the old Ware which has now disappeared but deserves a mention as it was still part of the scene in the 1920's about which I am writing. From Bowling Road, I walked to Christ Church Infants School in the mornings, back at midday and again in the afternoons via Kibes Lane and New Road As a small boy I always found Kibes Lane somewhat intimidating. The road was narrow and most of the dwellings were overdue for clearance. The half doors opened directly on to the pavement and the interiors were dark and, to me, threatening. I am sure the inhabitants were very decent people trapped in Dickensian conditions, but the atmosphere was depressing and I felt driven to walk on the outside of the pavement lest I be grabbed and hauled into one of the dark interiors, a thoroughly irrational and unwarranted fear, I am sure. Certainly, one family I knew quite well who lived in an erstwhile lodging house at the town end of Kibes Lane, were the Campkins, a cheerful and very pleasant lot.

Halfway along the Lane on the south side was the Jolly Bargeman public house and among its regular customers was Tom Cakebread, probably the last of Ware's working bargees. A nugget of a man with a weather-beaten face, Tom looked exactly the part. His days were spent with his horse trudging the towpath by the side of the River Lea, the horse hitched to a long towing rope attached to the barge, Tom looking every bit the tough and colourful character with which tradition has endowed the bargee.

At the junction of Kibes Lane and Bowling Road was the Ware Gas Works with a Mr Porteous as Manager. Our house and many others had gas but no electricity. Some of the house lights were just naked fan-shaped flames but most had "mantles" made of silky cotton which gave quite a good white light. I can still recall the pungent smell when a new mantle was burned into use.

Home Entertainment

A good proportion of homes had a piano, usually a second-hand one, and we were no exception. As I have mentioned, my sister played well and it was thought a good idea for me to accompany her on the violin. This soon proved to be a monstrous misjudgement - I had neither the talent nor the patience. We both took lessons from the Misses Bannister, a couple of genteel spinsters who lived at the top of Jeffries Road. One sister taught the piano, the other, poor soul, sought to teach the violin and the mandolin. I got nowhere fast. Scratching laboriously at "Twinkle, twinkle, little star" while my younger sister was able to play real tunes was more than pride could stand. For me, the most frightening aspect was that the Misses Bannister's pupils were expected to perform in groups at Church Fetes and the thought of making an exhibition of myself in public was unbearable. After running out of excuses for not participating I gave up the violin for ever!

"Wireless" was becoming a feature of life in the mid-1920's. These were very much "make your own" days and most people who took it up started with a "crystal" set. Contact with the piece of crystal was made with a "cat's whisker" which was a springy piece of thin wire. The volume and quality of the audible signal depended on finding a suitably sensitive spot on the crystal and much annoyance was caused if an incautious movement by a member of the family caused the cat's whisker to lose its advantageous position and the search for a fresh "sweet spot" had to be undertaken! The volume of sound obtained from a crystal set was just sufficient to activate a set of headphones.

My father progressed to a receiving set with a thermionic valve in addition to a crystal and with this the volume in the headphones was significantly increased. My cousin, Tom Dewbury, soon became expert and constructed radio sets with multiple valves capable of running loudspeakers. Originally these were basically headphone units with a magnifying trumpet similar to that of the gramophone. The tone was poor, but the increased volume meant that listeners avoided having to wear headphones. Radio opened up the world and we listened to many things including the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts. The British Broadcasting Company through its London station 2L0 set new standards of integrity in its news bulletins.

Everett Elliot

Our next-door neighbour at 27 Bowling Road was Everett Elliot, with his housekeeper. She, dear soul, had no teeth and shortened his name to what sounded like "Eb" so for some time we thought his name was Ebenezer. He was 71 years old when we moved there, which meant that he was born in about 1852 and had lived most of his boyhood in Wadesmill. He went to school in Ware and often got there by driving a pair of horses from the Feathers Inn in Wadesmill to the old Saracen's Head in Ware and reversing the process in the evening. These horses were part of the system for pulling the Cambridge coach "over the hills" i.e. to cover that section of the old Cambridge Road between Wormley and Puckeridge. I believe the coach, which alternated between Oxford and Cambridge, was running at least into the 1870's. John Rogers, the Baldock Street bootmaker, records that the coach was called The Defiant and belonged to a Captain Blyth. He states that on one occasion it stopped at a house then belonging to the Harradence family near to the Priory to allow one of the Harradences and his bride to alight on their return from honeymoon.

Everett Elliot had a wonderful memory and, apart from recalling so many local events, could recite long stretches of poems of Thomas Hood. "The Song of the Shirt" was his favourite. How wonderful it would have been from the point of view of local history if there had been tape recorders then to have captured his many memories. He also took me for the first time to Thundridge and Wadesmill via Musley Common, Poplar Green, Gardiner's Spring and Thundridgebury. A wonderful walk but a bit of a test for a seven-year-old. By the time we moved to Bowling Road Everett had retired from his nearby wheelwright's business which, after an interval, was taken over by a Mr Bishop, one of whose sons, Albert, has a radio/television shop in the High Street. It was quite a sight to see the metal tyres being heated by a circular wood fire until they were red-hot and then hammered by hand onto the wooden cartwheels, at which point water was played onto them to make them shrink and also to prevent the wooden wheels from catching fire. The smoke and steam made quite a sight.

Local Shops

Many of the immediate requirements by way of food (and sweets!) were got from Weatherall's small shop a little way along Bowling Road from us and from whence, in the winter, we bought the Saturday evening "Star" which gave all the football results printed under "Stop Press" a remarkable achievement in less than an hour from full-time. And it cost Id! Another feature of winter Saturday afternoons was the arrival of the muffin man, tray on head, the muffins reposing on the green baize with which tray was lined, ringing his brass bell to announce his arrival.

The family of Fisher ran a dairy business on the corner of Bowling Road and the then un-made King Edward's Road and I often watched fascinated as the milk cascaded down the cooling machine. One of the sons was a 'bus driver and a motorcycle enthusiast and he eventually bought a beautiful Norton bike which he rode slowly up and down the road. Whilst most other motorbikes were rather crackly things this particular machine broke new ground with its throbbing, throaty sound.

Youthful Wanderings

One particular reason why so many of us oldies sigh for those days was the freedom we children had to wander far and wide without fear of molestation, which is unfortunately not the case today. It is true that occasionally one of the children started the story "There's an old man up there!" and sometimes there was - usually an old vagrant whiling away the time until the casual ward at the workhouse opened. But I never heard of any child coming to harm in these circumstances.

Consequently, as far as I was concerned, I was able to wander widely from the age of about 8 or 9 years indulging my favourite pastime of bird's nesting. Nowadays, with birds becoming scarcer as a result of insecticides and a shrinking habitat, taking eggs from most birds is illegal and, in today's circumstance, rightly so. But in the 1920's and '30's most boys of my acquaintance stuck fairly rigidly to a code which had developed. Firstly, no self-respecting collector took an egg of a species which they already had. Secondly, there was a belief that there should be at least three eggs in a nest before one was taken because the bird would notice if, say, one out of two were taken and would desert the nest. I think the truth is more likely to be that the bird's faithfulness to the clutch increases the nearer she gets to the time of hatching. So, most of us kept a watch on the nest until the bird had laid a full clutch before taking one (if we needed it).

There was always a strong aversion to "lugging" nests (simply destroying the nest and its eggs). This was never done by a serious collector. The common way of preserving eggs was by making a pinhole either end and blowing out the contents. Considerable skill and patience were involved in finding the nests, particularly the rarer ones, and there was a lot of handed-down wisdom. One needed to know the sort of habitat associated with particular birds and then to observe in stillness their unobtrusive comings and goings. Looked at 60 years later most people would regard birds-nesting with repugnance, but one should really see the past in the context of its own time. In those days we stood proudly to attention at school on Empire Day yet looking back we would say that it was immoral! I am sure that most of us who collected eggs then are now supporters of the RSPB.

Most of my youthful forays began with the path which led from the top of Bowling Road up by the side of the allotments to Musley Common, up towards the water tower then right, eventually coming to what we used to call "Dark Lane", thoroughly exploring the fields, banks and hedgerows. It was a wonderful world of linnets (a variety of finches), yellow hammers and skylarks in addition to the commoner species which, thankfully, we still see in our gardens today. I was always grateful for what I learned about birds as a boy from a friend of those days, "Adgie" Williams, who lived over Musley and whose adopted father Mr Andrews worked for Harry Frost, the Baldock Street tailor. My mind jumps - quite disconnectedly - to a shop a little further along Baldock Street occupied by Stanley Caudle the "SPQR Draper". It was a long time before I learned that these initials stood for "Small Profit Quick Returns"!

A goodly proportion of us boys were members of "gangs" and we had headquarters in secure places in hedgerows and copses. Most powerful in my time was the "Johnson" gang who met in a spinney in the corner where Little Widbury joins the Wareside Road. They were somewhat older and the rest of us kept clear of them. In fact, all the gangs were quite benign and merely outlets for youthful romanticism rather than violence.

In summer we spent, as children, quite a lot of time along the West Fields where the main attraction lay around what was, I believe, the original course of the River Lea before the new channel was constructed to facilitate the barge traffic. The new channel departed from the old at the Tumbling Bay. Before the Ware Swimming Pool was built in the late 1930's, the only places to swim, or just bathe were the rivers. The Lea was dangerous unless you were a good swimmer and those who were spent a lot of time diving off iron footbridges. The rest of us contented ourselves with splashing about in the shallower waters. In this area we frequently saw a strange and eccentric elderly lady who seemed to be always gathering wildflowers. She dressed in Edwardian style with always the same straw bonnet. I eventually learned that she was a Miss Hall, and she lived in the High Street next to the Bell public house. She occupied the living quarters of a disused shop, with brown lattice shutters which were kept permanently closed. It was said that the premises were full of dried flowers and herbs. Mercifully she never dropped a match!

Christ Church School

Christ Church School, which I attended from the age of 5 to 11 years was, I suppose, typical of the elementary school of those days. The Head of the infants school was Miss Grace, a rather serious but dedicated teacher whose appearance was not helped by a goitre which moved perceptibly when she became agitated. Usually, one progressed a form a year, but it was possible to advance quicker if one got good results. Somehow they must have lost track of me because I was in the "Big Boys" at 9 years among the 13 and 14 year olds, which helped considerably when I took the entrance examination at 11 years to qualify for the former Musley Central School.

I need to say a little about Christ Church "Big Boys". In my time, there were three forms, one in a separate room taught by a mannish woman named Miss Hyde. She was the first lady cricketer I had come across, and she produced her own bat and taught us cricket in the occasional games period. The middle class was in the charge of Mr Benjamin Gale, a returned soldier of the 1914-18 War. Special arrangements had been made to give ex-soldiers some training in teaching and Benjamin Gale was one such. A kindly man, greatly taken advantage of by some of the more uncouth pupils, he was another friend of my father from among the customers of the Jolly Gardener and early on gave me private lessons in "joined-up" writing.

The Headmaster, Mr Mackinson, took the top class - when he was there, which wasn't very often. He looked a sick man and probably was. His class and Mr Gale's class were both in the same large room which was divided up by a gangway in the centre. Because of the Headmaster's more or less permanent absence poor old Gale had to try to keep some sort of order among upward of 60 boys! Teaching hardly came into the question – he was at his wits' end just to keep the noise level down to something reasonable. When things were particularly bad Mr Gale would issue out pencil compasses to one class or the other - most of us liked drawing geometrical patterns with them. Otherwise, comics and boys' magazines were read from cover to cover. When Mr Mackinson did come in, rarely before 9.30 a.m. anyway, the scene was completely different. Mr Gale, from his position between the classes, was on permanent watch through the never-closed door for his arrival and held up his hand as soon as the headmaster entered the playground. Silence fell immediately and "normal" teaching took place. It has to be said that the two classes went in fear of "Old Mac." He did not often use the cane, usually his method of punishment was a severe slap across the face which seemed to be more psychologically damaging than the cane would have been.

It was then fairly routine for Mr Mackinson to address both classes for ten minutes or so. The subject was always the same, "Old soldiers trying to be teachers", and poor Gale had to stand there to hear vilification being heaped upon his head, without his name actually being mentioned. Even though there were some very rough boys in these two classes, none of us enjoyed having to listen to these diatribes. We all realised that with the headmaster's dreadful absence record, Mr Gale was in fact earning his salary for him in return for these insulting strictures. The whole situation, when I look back on it, seems quite incredible, but the reader can accept that It was exactly as I have described it.

The noise level was such that teachers in adjacent rooms trying to teach the infants frequently banged on the partition walls to try to get it reduced. On one occasion Miss Hyde had had enough of it, came through into the big room and hauled a boy (Taylor), who was making a lot of noise, into her room and stood him in a corner. Seeing this, his elder brother ran out of the top class, crossed the playing field and fetched their mother from their house in Vicarage Road. She seized the unfortunate Miss Hyde, held her in front of her class and made the younger boy who was the cause of the trouble kick her on the backside.

The Chairman of the School Governors was printer and Chairman of the Bench Mr A.H. (Dolly) Rogers, always well dressed down to the spats which he habitually wore. Once a term he came to the School and checked the registers. He read out the names and we had to answer "Here, Sir!" Although a very intelligent man, he frequently stumbled over a name (possibly deliberately) and always joined in the consequent laughter. Dolly Rogers was universally liked and respected throughout the town.

The then Vicar of Christ Church was the Rev. Frank Hobson and he frequently came to the School and took a scripture period. No doubt a good and pious man, he was a little too serious for us. But once or twice he used a saying which I have carried in my mind ever since and it is as applicable today as it was then - maybe it needs even greater emphasis!

"First I learn to be governed.

Then I learn to govern myself

Then I learn to govern others.”

One can sense the Victorian ethos of discipline by the use of the word "govern", but the progression in the growth of responsibility as a person matures is, I think, admirably expressed.

In the summer of 1929 I caught scarlet fever, as did many other children in those days. This meant six weeks in the Isolation Hospital on Gallows Hill, Hertford. The first two weeks we ran a temperature and had to stay in bed - with doses of the hated liquorice powder to purge us. After that followed a month of boredom waiting for the skin to peel and the infection to clear. Each Wednesday and Sunday during that period, we were taken out to stand in a line a safe distance back from the main gate, the other side of which stood our parents, and we shouted to each other the sort of banalities appropriate for the occasion. The less fortunate caught diphtheria, the consequences of which could be much more serious, and they were housed in another building but on the same site. When we were discharged, we and our clothes had to be fumigated in an extremely hot corrugated-iron roofed hut which, I remember, ruined my braces! Coming out of the Isolation Hospital meant a complete change of life for me as my father had, in the meantime, taken over as landlord of the Windmill public house at Thundridge. This meant village life, which I loved.

Musley Central School

Prior to getting scarlet fever, I had taken the entrance examination for Musley Central School. The alternative was to take that for Hertford Grammar School for Boys. My father, probably as a result of 22 years on the lower deck in the Royal Navy, retiring as Chief Petty Officer, had a strong aversion to snobbery and probably sometimes imagined it where it didn't exist. He had a particular antipathy to certain tradesmen's sons who were paying pupils at the Grammar School. And so, in our family it was a place to be avoided in favour of Musley Central School which, under its Headmaster, Mr. A.E. Evans, had a good name locally. When the examination results were announced in the "Hertfordshire Mercury" it was pleasant to read that I had achieved top place. Shortly after starting there Mr. Evans spoke to the headmaster at Hertford on my behalf and I was offered a transfer, largely unheard of in those days. Quite stupidly and without consulting my parents, I turned it down on the basis that I was nicely settled in at Musley and was enjoying my football. Looking back, I can see how silly it was to leave such an important decision to an eleven-year-old.

Soccer was strong at Musley. We played on the Ware "A's" pitch on the Meads and on Allen & Hanbury's Sports ground adjacent to the factory. The latter was a splendid pitch, with excellent changing facilities whereas the Meads in winter could be awful. The ground frequently waterlogged, and with changing in the open air by the railings. Some days one's fingers were almost too cold to do up shoelaces. Mr Evans was a very capable Headmaster who stood no nonsense from anybody. He had a splendid voice, having previously sung with a leading Welsh Opera Company. He had also played professional football for Aston Villa in their great days just before World War I. The story was that this provided him with the means to attend college. He never interfered with school football. The only time I saw him kick a ball was to demonstrate a corner-kick which, unbelievably, flew straight into the net! For most of my time football was in the capable hands of Bob Whitaker, the Maths Master who came to us fresh out of Manchester University. He was soon playing for Ware Town FC and after a time became their captain. The girls' winter game was netball and in the summer, they played stoolball and the boys cricket on the Allenbury's ground. At the School there was a fives court which was always in use albeit we played with bare hands and a tennis ball.

The catchment area for Musley Central School stretched as far as Buntingford in the north and Wormley in the south. Pupils came from Benington on the one side and Widford on the other. Some of the "country" pupils travelled by bus but many cycled long distances. School started at 9 a.m. and continued, with a break for lunch, until 3.45 p.m. The whole school had single subject tests under examination conditions every Wednesday afternoon. On the day each form had a different subject and we were allotted seats in any part of the School. The results were taken seriously, and the top and bottom marks were commented on by the Headmaster at assembly. Credits (or black marks) were awarded for the respective "Houses": Wilberforce, Shackleton, Excelsior or Dreadnought. I have no doubt at all that these weekly tests helped keep both staff and pupils up to scratch. Mercifully, the Wednesday test period was followed by sport. The School buildings were old and cramped - the top form was accommodated across the road in the Headmaster's house. But this seemed in no way to interfere with the learning process. About 1932 the School was merged in with a new secondary school on the Christ Church site. Mr Evans retired, and Mr Braybrook was appointed Headmaster.

Chapter 3 Out To Work

Ware Rural District Council

I left school in 1934 at 16 and started work in the Rates Office of the Ware Rural District Council which, together with the Surveyor's Office, was housed at a former private house - No. 97, New Road. The Rating Officer was Jack Burnett. The actual collection of the cash was farmed out to a number of people throughout the Rural District who were paid a commission on their collections. Up to the point at which I joined, a Mrs Rookby, who lived and worked from No. 93, New Road, had been responsible for the Urban Council's collections and for those in some of the parishes near the town but not in the Rural District. The work was largely done by her assistant, Bert Wright, who was soon to be appointed full-time collector for Ware Urban District Council. Mr R.J. Suckling was similarly appointed for the Rural Council. I have already mentioned Bert who had a superb baritone voice and a splendid presence which he put to good use in the St. Mary's Church Choir and in local operatics. Some knew him as "Poo Bah" as a result of his playing that role in Gilbert & Sullivan’ The Mikado. His good friend Clifford Parker, a Relieving Officer under the Poor Law, sang tenor with Bert in the Choir and the Operatic Society.

Jack Burnett was a keen fisherman and, in those easy-going days, it would be difficult to know at any time whether he was out checking valuations or casting a line! Either way, as I was the only other one in the office, it meant that I had to learn about rating as quickly as possible. This was made a little more complicated by coinciding with the re-valuation of properties and therefore with the introduction of a new valuation list. A firm of specialist valuers had been engaged for this and they had valued all industrial and commercial premises and had done specimen valuations of dwelling-houses in each parish. The specimen prices per foot so obtained were then applied to the remaining houses by Jack Burnett. So I had an insight into the practical aspects of valuation which I would not otherwise have had. I also found myself keeping the Council's housing rental records.

I recollect that the cheapest houses were some at Dane End with an inclusive rental of 3s.2d.!

Going out to work meant that I was entitled to smoke which virtually all my friends did. On my first morning Jack Burnett went up to the Rifle Volunteer as soon as it opened, and I followed later up to Scott's at the corner shop, where I bought a packet of Gold Flake cigarettes and a box of matches. I should add that Jack Burnett rolled his own and smoked like the proverbial chimney so the office was usually fairly smoky. Back in the office I lit up. I was puzzled and disappointed. I had expected something pleasant whereas I found myself spluttering and my eyes streaming with tears. Somehow, I got through the first cigarette but stopped part-way through the second. That was my first and last serious attempt at smoking. Since then, I have smoked the very occasional cigarette and I do enjoy a cigar, but I consider myself very fortunate never to have developed a taste for it. This was particularly the case when I later became a prisoner-of-war and was able to swap my Red Cross cigarette ration for much more useful things.

From the Rates office I had occasional contact with Harry Stutchbury who worked at Gisby's. Hugh Gisby was Clerk to the Ware Rural District Council and after 18 months working direct for the Council, I was offered a junior job in Gisby's Office, then in the Old Town Hall in Rankin Square (they later moved to Baldock Street). I took the job and was immediately in a new rapid-learning situation! Gisby's was probably one of the last examples of a country firm of solicitors holding a number of part-time public appointments.

Gisby & Son, Solicitors

When I joined in 1935 there were two partners - George Gisby, who was over 90 and his son, Hugh, in his 60's. George Gisby had only recently given up being part-time Clerk to the Urban Council. Leslie G. Southall, who had hitherto worked at Gisby's predominantly on Urban Council work, had been appointed the first full-time Clerk of that authority. George Gisby, although he still spent some hours everyday in the office, only saw a few old clients. One of these, the Rev. Harvey, Vicar of Amwell, called in whenever he was in town. Many years previously he had been at school at Haileybury with George and they met more to reminisce than to do business. What memories they must have had, back into the 1860's! Another of George Gisby's old friends was George S. Pawle of Widford who had a lovely cricket ground attached to his house on which country house and village cricket was played. Mr Pawle had by this time become partly eccentric and on his notepaper was printed:

"Address reply to G.S. Pawle - not Mr or Esquire"

George Gisby knew me as "Tweedy" because of my jacket and never bothered to learn my real name. But he was a delightful old Victorian gentleman out of whose office I quietly tip-toed on those occasions when I found him having an afternoon nap. He frequently smoked a cigar and drank the occasional sherry and his office had the attractive atmosphere of mellow old age.

At the time I joined, Hugh Gisby was Clerk to the following authorities and organisations:

- Ware Rural District Council

- East Herts Guardians Committee

- Hertford & Ware Joint Hospital Board (Isolation Hospital)

- Hertford Assessment Committee (Appeals against rating assessments)

- Buntingford Magistrates

- Old Age Pensions Committee

- Local Education Sub-Committee

He was also Superintendent Registrar and the firm was Collector of Tithes for Queen Anne's Bounty and Trinity College, Cambridge. The firm, of course, also had its practice as Solicitors.

There were five lady clerk/shorthand typists whose names I remember as Mrs Albany and the Misses Smith, Bailey, Inwood and Edwards. Apart from these, the sole staff to do all the administrative and financial work of these bodies consisted of:

- Harry Stutchbury - paid as Assistant Clerk to the RDC and Guardians Committee.

- Albert Auger (from Much Hadham) - largely concerned with the firm's Accounts.

- George Gilbert - a recent appointment for Guardian's Committee work.

- Lionel Tarplee (from Hoddesdon)

- Myself - the "Poor Filing Clerk" referred to in Henry Page's Reminiscences of Ware 's Past No. 7.

Harry Stutchbury (who later became Clerk to Welwyn RDC ) had his own office. The rest of the male staff sat round a huge table in what was known as the Board Room. The heating was by one large open fire which meant that the two on that side of the table had to have wicker shields fitted to their chairs to protect their kidneys from the heat, whilst we on the other side remained cold. There was one telephone in the room and, largely out of deference to George Gisby, a cluster of speaking tubes.

These tubes were, of course, the pre-runners of internal telephones of which in my time there were none. The speaking tubes, which we all hated, were held in a rack and in the end of each was a whistle with an indicator. The idea was that if you wished to speak to anyone in another office, you removed the whistle from the appropriate tube in your office, then blew sharply into it. At the far end of the tube the whistle sounded and the indicator, a small plunger, jumped out for a split second. The person at that end removed what they thought was the appropriate whistle, announced their name, then smartly transferred the tube to their ear to hear the caller's message. The practical problems can easily be imagined:

Firstly, someone at the receiving end had to glance up very quickly to see which indicator had jumped.

Secondly, rational conversation was difficult because it depended upon the person at one end speaking into the tube at the time the unseen person at the other end had the tube to their ear and vice versa.

There was a further difficulty in that in George Gisby's case, blowing the whistle and activating the indicator at the other end of some 35 feet of tubing was asking a bit much of his 90-year-old lungs. In any case the old Gentleman's voice was difficult to hear in the ensuing conversation. Mercifully, the system was on its way out and was more or less limited to use by George Gisby, so that watching for the indicator became less and less necessary. What was tending to happen if a whistle blew was to answer it with "I'll come down now, Sir!".

Another relic to be found at Gisby's was the letter book. Letters outward were copied by passing them through a sort of mangle against a roll of specially dampened paper rather like a kitchen roll. Special blue typewriter ribbons were used, and quite good copies were produced. The copies were guillotined in the morning by which time they had dried and were filed in date order in letter books. Thank goodness the junior girl had the job of indexing these. The obvious drawback was that the subject files only contained letters inwards, noted up about any reply.

At the beginning of my job at Gisby's, filing was a nightmare! As a junior it was difficult enough to know which of the bodies a letter referred to, let alone which subject file to put it on. When the filing got behind, which it frequently did, a daunting heap of paper piled up in the cupboard in which I used to hide it. Probably my worst occasion was when I was asked to produce a Ministry Loan Consent for £20,000 enabling the Rural Council to borrow that sum to build a new sewage works. I eventually found it of course, but for a 17 year old it was an extremely worrying hour or so. I felt as though I had actually lost £20,000 instead of a piece of paper which could, if necessary, have been replaced.

Gradually, of course, I became more knowledgeable and more confident. I learned which bills were payable by which body and who should be authorising them and I attended Finance Committees ready to answer any questions. In those days it was customary for cheques to be signed by two members and countersigned by the Clerk. I began to find my way about the Poor Law Act 1930 and to understand the basics of the Law of Settlement. Put at its most simple, people acquired "settlement" for Poor Law purposes by residing in a place for 3 years as well as in other ways and, pending this, any poor relief paid to them was recharged by the paying authority to the Poor Law authority in whose area they were last settled. So, a Poor Law authority paid for relief elsewhere for its own "non-resident" poor and claimed on other authorities for payments it made to its "non-settled" poor. Claims and payments flew in all directions!

Before long I acted as Clerk to reviewing Sub-committees of the Guardians Committee, at which the Relieving Officer for the area (Cliff Parker for Ware Urban and Ware Rural and other officers for the Hertford and Cheshunt areas respectively), reported on regular cases. Most of them were elderly, some living in alms-houses and most of their names and circumstances well known to members of the authority. "Oh! how is old Mrs Smith, does that son of hers help her at all?" would be a typical sign of caring by a member, which I found rather heart-warming. The amounts of relief involved in these cases appear now to be trivial, most were 2/6d. per week supplements to the 10/- State Old Age Pension, with usually double this figure for the winter months to help with extra fuel. Apart from these straightforward and regular cases there were the more contentious cases of families who had fallen on hard times. Some were given relief in kind, that is in grocery tickets. This was invariably so when the husband was known to spend money on drink. One of my more tedious jobs was to check for payment the bills sent in by tradesmen for the goods they had supplied against these tickets.

Western House in Collett Road ("The Union" as it was usually known) housed a hospital for the chronically sick poor and provided overnight lodging for the vagrants who in those days were permanently moving about the country. The name "Union" was derived from the previous system of Poor Law under which parishes acted jointly for certain purposes as "Unions of Parishes" and were funded through the "Poor Rate". Among the older people one frequently heard the expression "on the Parish" to describe a person receiving poor relief. From 1930 Poor Law functions became the responsibility of County and County Borough Councils and were financed as part of the General Rate. As now, the Counties' requirements were levied and collected by the constituent district councils as rating authorities.

That part of Western House which dealt with vagrants was commonly known as "The Workhouse" as it had been in Dickens' time. Vagrants came in around about tea-time and were given a meal and a place to bed down. In the morning they were given breakfast and usually had some wood to chop before being sent on their way at 8 a.m. to tramp to the next workhouse. Northwards it was at Buntingford. Hence, living as we did at Thundridge by this time, we saw the first of the "roadies" at around 8.45 a.m.

The first houses past the "Sow & Pigs" public house were always being bothered by them for "..a dust of tea" or "..a mite of sugar" and "..some hot water if you please". Whilst the majority of vagrants were rather sad and inadequate people, there were some rough diamonds among them, and fights often broke out at the workhouse. Sometimes these were dealt with summarily by the Master wading in with his fists. The Muncer brothers, more or less permanent residents, were notorious for this sort of thing and were frequently up before the Bench on some charge or other.

The pattern generally was for a joint appointment of Master and Matron, held by a husband and wife team. In those days the incumbents at Western House were a Mr and Mrs Martin. It was a tough job and Mr Martin was a tough egg. He brooked no interference with his "empire". In some places Masters' "perks" by way of diversion of stores were considerable as was the misappropriation of inmates' pensions, but although there was no suspicion of this at Western House, had it been the case the Master' s control of everything that lived and moved there would have made investigating it a formidable task!

Meetings of the Guardians Committee and the Rural Council were held at Western House, as were their annual audits by the District Auditor. On meeting days and at audit I was pressed into service, cycling between the office and Western House with books and files, although the bulk of them were transported on a hand truck pushed by a couple of long-term residents there. I had a great fear of going into the audit room lest I should be asked a question about the accounts, which it was extremely unlikely that I would be able to supply a credible answer. I found it similarly disconcerting to have to take something into a meeting in progress of either the Council or the Guardians Committee and to find the eyes of all the local Great and the Good turned on me.

In those days it was customary for prominent personalities to head local authorities. The Ware RDC had as its Chairman Mr G.J. Pearce of Stanstead Abbotts and he served as such for a goodly period and was much respected. The Chairman of the Finance Committee was one "Tubby" Stevens, in quite a different mould. He smoked a really filthy pipe and filled the room with smoke. The Chairman of the Guardians Committee was, in my time, C.W. (Charlie) Ward. Charlie was a maltster and very much "Hail fellow, well met". His office was off the High Street, near to the Priory, and his ringing voice could often be heard in that area, particularly as he always used a bicycle. He was a charming man and greeted - and was greeted by - everybody he met, labourer or toff. His home was in Collett Road near to Western House. Another prominent member of the Guardians Committee was Mrs H.B. Webster who originally lived at Sacombe Park but later moved to Sprangewell at Thundridge. After we moved to Thundridge I got to know her well and found her a charming lady.

From 12 noon on Saturdays there were frequently marriages to perform as part of the Superintendent Registrar's function. So, the Board Room table had to be cleared of its usual mass of papers and the party ushered in. If they were short of a witness I, as the junior, had to stand in as one notwithstanding being under-age. In summer I played cricket on Saturday afternoons, so I found the delay in getting away irksome. In those days Registry marriages (apart from the rich and fashionable) were usually of last resort, and often the bride was glad to rest her tummy on the table as she stood, in which case it was fairly certain that another entry would appear in a few months time in the Register of Births!

One of the more unusual functions we had at Gisby's was the collection of tithes. These were payments originally due from landowners and payable to the Church although over the years the rights to them had, in many cases, passed by gift or purchase to charities and other bodies and persons. Annual tithe payments were commuted under the Tithe Act 1936 but prior to that Gisby's collected payments on behalf of the charity Queen Anne's Bounty and for Trinity College, Cambridge. The payments were in respect of plots of land throughout the district, mostly farm land. The farmers hated paying tithes, particularly in the 1920's and 1930's when the farming industry was very depressed. We had large tithe maps which had to be unrolled when there was a query. Generally, they had deteriorated to the point at which the paper was flaking away from its canvas backing and in many cases it was almost impossible to identify the plots in respect of which we were demanding payment.

Chapter 4 End of Story